Farming and Conservation Go Hand in Hand in Tasmania

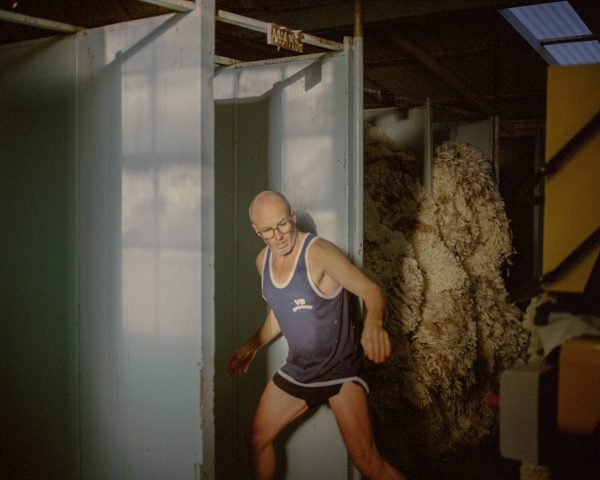

In Tasmania, one fourth-generation merino wool farmer is interweaving agriculture with ecology. Julian von Bibra, whose family has tended to the same land for generations, embodies a growing movement among growers who recognize that preserving what’s left of their land’s natural heritage — from safeguarding precious native grasslands to monitoring threatened animal species — will be integral to ensuring a resilient future for generations to come. Words by Whitney Bauck, with photography by Kin Chan Coedel.

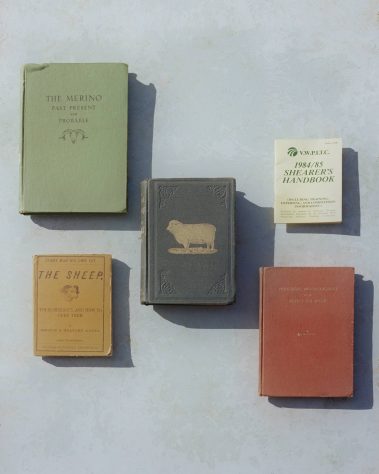

Julian von Bibra’s family has been farming the same land in Tasmania, an island off the southern tip of Australia, for four generations. Von Bibra grew up watching his parents raise sheep on the land, and though they never pressured him to follow in their footsteps, he felt an “enormous sense of connection to our community, to our land and to growing merino wool.”

It was that sense of connection that spurred him to start looking for ways to turn the farm, called Beaufront, in an increasingly ecologically-minded direction.

Though von Bibra feels proud of his farming business, which includes grains, pharmaceutical poppies and cattle alongside a flock of Responsible Wool Standard certified merino sheep, he’s also honest about the ways that the introduction of European agriculture has wreaked havoc on people and landscapes in Tasmanian history.

In addition to settlers’ “very dark past” of violence against Aboriginal Tasmanians, their approach to farming over the last 200 years has altered local landscapes by clearing trees, introducing fertilizer, replacing native grasslands with perennial non-native grasses, overgrazing the land and fragmenting crucial habitat. But von Bibra believes that the power that today’s farmers yield on the land can be channeled into practices that are not just less harmful, but actively helpful in protecting biodiversity in Tasmania today.

“There are areas of these native grasslands that still exist, and so they become very precious,” he explains on the phone one cool June morning. “They’re [almost] all privately held, which means farmers in our region have a role in ensuring that we don’t lose them.”

Von Bibra is trying to take that responsibility seriously on his own land and encourage his neighbors to do the same: He and his wife Annabel have put 40 percent of their property into some form of reserve. “We need to take responsibility as land managers, not just for our annual profitability, but in making sure we don’t erode our natural capital,” he says. “It’s that juggle between running an agricultural business, and not losing all our biodiversity, as this wealth of native grasslands is unique and needs protecting. Getting that balance right is a real challenge.”

Harnessing partnership for land restoration

To help tackle that challenge, von Bibra has enlisted the help of a handful of local community, non-profit and university partners. The farm has experienced “small wins” in the form of partnering with local Aboriginal community groups to re-introduce cultural burning onto parts of the land, though von Bibra notes that it’s a “work in progress.”

“I think the early shepherds used to try and mimic Indigenous practices and probably got it wrong. We’re picking up the pieces of a culture that is not well documented or understood, and trying to adapt modern farming techniques around that,” he says. “There’s been a lot of loss, a lot of hardship and a lot of pain. We have to firstly acknowledge that, and then respect the existing members of the community and try to re-engage with them — it’s a delicate task.”

One of the most significant partnerships on the land is a program called the Midlands Conservation Partnership (MCP), a project of the non-profit Tasmanian Land Conservancy. The MCP works with farm owners in the area to protect and manage critically endangered native grasslands and increase biodiversity. Manager of the program Pierre Defourny explains that many of these grasslands actually benefit from moderate grazing, having co-evolved with native grazing marsupials like kangaroos and wallabies, which makes working with sheep farmers a natural fit. “These grasslands do need some kind of disturbance; you can’t really just set them aside and forget them,” he explains.

Taking part in the Midlands Conservation Partnership

On Beaufront, 750 hectares are currently under a conservation agreement with the MCP. It comes with certain restrictions about how the farmers manage the allotment — they can’t clear or fertilize it, and they’re obliged to treat and control weeds — but other than that, the agreement is mostly outcomes-driven, giving the land managers a fair bit of choice and agency.

There are four key outcomes that Defourny and his colleagues look for to indicate that a farmer is managing a native grassland responsibly. The first is to see that the number of threatened animal species is being maintained or increasing — a crucial factor on an island like Tasmania, known as the home of species like the Tasmanian devil, which live nowhere else in the world. The second is for the diversity and cover of native plant species to remain stable or increase, while the third looks for the diversity and spread of introduced species to decrease. And finally, the MCP asks that every farmer it partners with report to the project about how they’ve approached management on the land.

Different farmers get involved for different reasons: smaller farmers might be drawn in by the financial incentives the MCP offers participants, while larger farmholders might be more interested in having a compelling sustainability story to tell their customers. For other farmers, Defourny theorizes, it’s just good old fashioned peer pressure — with a positive spin — at play.

“It’s not just a conservation program. What we are really trying to do is create a community of farmers who are interested in conservation, and who care about it. We are trying to change a social norm in the region,” Defourny explains. Von Bibra and two of his neighbors who have long been influential landowners in the community, and who were already more “conservation-minded” before the program started, he adds, helped “convince other farmers to join the program throughout the years.”

Sharing learnings with neighboring farms

The more neighbors involved, the better: Landscapes don’t stop and start where property lines begin and end, so being able to work together with neighboring farmers to create unbroken conservation areas helps create wildlife corridors that are crucial for endemic species’ survival.

And if the Von Bibra’s neighbors’ are looking for more inspiration on how to prioritize the sustainability of the landscape without sacrificing their ability to run a working farm, there’s plenty more where that came from. The pair have also carefully monitored the size of their sheep herd in drought years to make sure that the animals don’t overburden the land with excessive grazing, planted shelterbelts to reduce wind erosion and provide more wildlife habitat, and partnered with a nearby university and WWF Australia to monitor a population of Eastern quolls, a species of adorable spotted marsupials.

Von Bibra’s convinced that not only is working toward conservation the right thing to do, it’s the smart thing to do for any farmer that still wants their land to be viable for the next 200 years as climate change, market pressures and extreme weather continue to throw new challenges their way. “The world is changing, and we need to be adaptive and prepared to move with it,” he says.

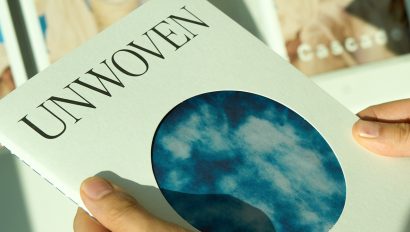

Explore the FUll Series

Farming and Conservation Go Hand in Hand in Tasmania

Kin Chan Coedel was the winner of our 2023 photography competition with Magnum Photos, which called on photographers to explore the visual stories that take place when fibers and materials are cultivated, created, spun, woven, sewn, loved and cherished – gaining cultural and emotional significance through the journey.