Planting Cotton Forests on the Edge of the Amazon in Brazil with FARFARM

Words: Yessenia Funes

Images: Sofia Terçarolli

Environmental journalist Yessenia Funes meets the women at the heart of an agroforestry project in Irituia, Brazil, where cotton plants are grown among native fruit trees.

In the Brazilian town of Irituia, the sun is virulent – as it tends to be this far north in Brazil. It’s early August, and the local factory workers are going about their day-to-day jobs. Their facility processes fruits and plants for organic farms around the region of Pará, a Brazilian state that sits nestled on the Amazon rainforest’s northeastern edge. You can feel the jungle breathing into the community as children play in a stream that’s no doubt linked to the Amazon basin.

At this factory, there’s none of the rust, steel, or men one might imagine. Instead, bright teal walls and two towering doorways stand over 10 feet tall. Inside, the floors are dotted with dried-out shells of tucumã fruit. Four women are hard at work, laughing and smiling as they prepare the fruit to be turned into oil for skincare products. “Having women working here is marvelous,” Eliete Nunes, lead producer at the factory whose hands are covered in black sticky pulp and shells from the fruit, said in Portuguese through a translator. “Farming gives meaning to our lives.”

This is the beauty of Cooperativa D’Irituia, the farm cooperative that owns and runs the factory. It’s women-led. And in a few short months, this safe space will be devoid of tucumã fruit, which grows on native palm trees. In its place, the factory will be full of organic cotton – where machines will gin the fiber and shape it into bales to transport.

Cotton has infused new life into the cooperative. Since 2021, it has been partnering with FARFARM, a start-up on a mission to reforest the Amazon biome, invest in smallholders, and clean up the fashion supply chain.

FARFARM works with a flourishing network of local farmers and agricultural organizations like Cooperativa D’Irituia to grow cotton organically using agroforestry practices, before buying the bales to sell to French shoe company VEJA.

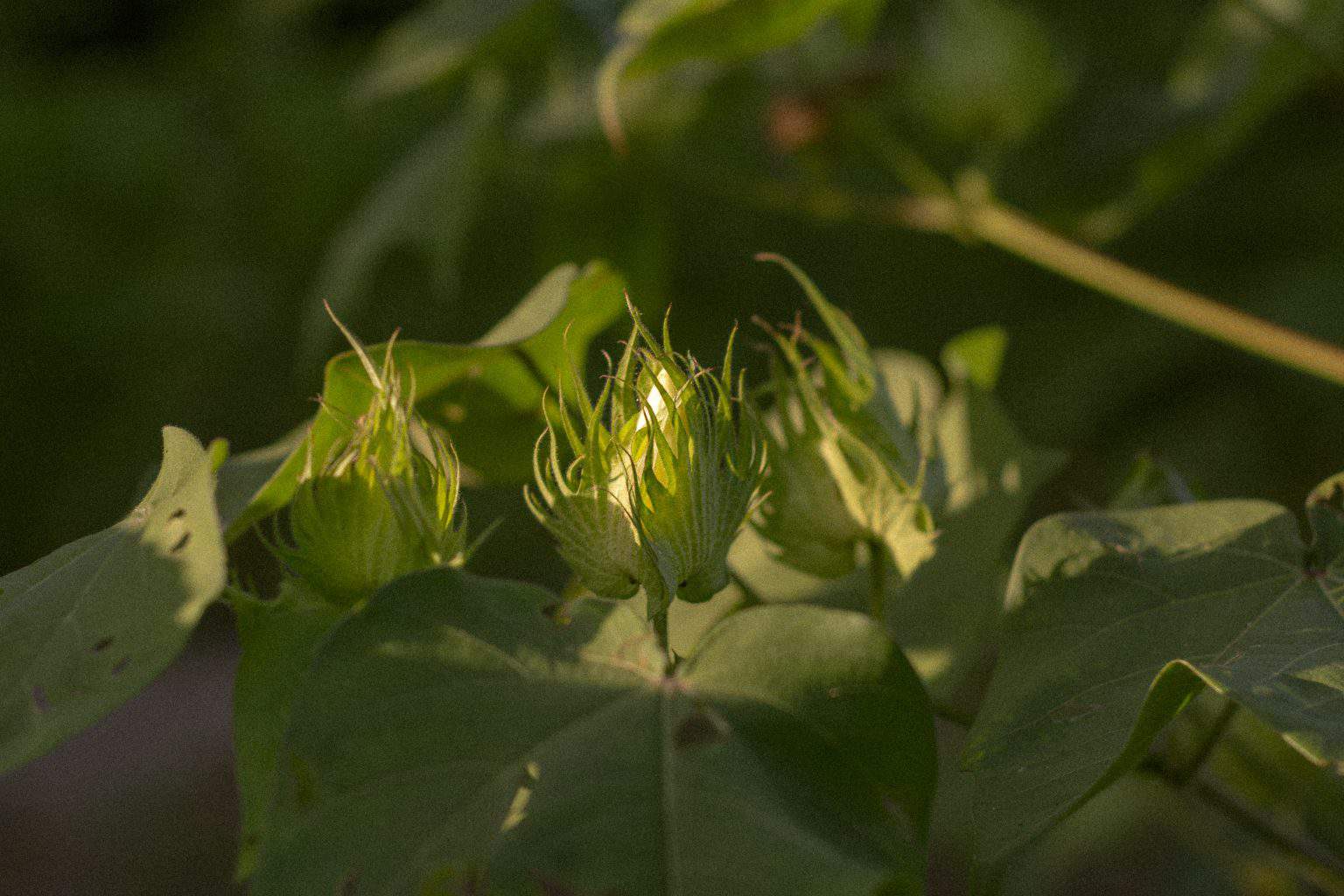

Agroforestry involves creating an ecosystem of plants and trees that bring diverse benefits to both the land and community, making for a farm that is at once a forest and a food system. Because of this approach, many local farmers grow cotton and native trees, like tucumã, just feet apart from each other on their land. Together, the crops help enrich the soil and provide farmers with multiple income sources.

“Having women working here is marvelous. Farming gives meaning to our lives.”

While many farmers bring their products to Cooperativa D’Irituia’s factory for processing, it is just one partner among FARFARM’s growing web of producers. To help scale this model, the start-up also supports local initiatives that help to build out the region’s network of organic growers working with agroforestry. And throughout the region, women are at the helm of revitalizing the Amazon one cotton crop at a time.

Take Lenise Oliveira, a farmer from the municipality of Santa Barbara. Oliveira is the founder of Ecovila Iandê – a forest village where she and her husband live and train local farmers about agroforestry. The 58-year-old former zoo technician became an agroforestry expert after buying some land in 2011.

“Every farm should be led by women,” said Oliveira outside her guest house, engulfed by the forest’s melody of rain showers and bat calls. She is a small but stately woman who wears glasses and often walks around with a machete strapped to her tool belt. She keeps her style simple and practical, but she’s always wearing two black rings on her left hand. Her husband cut them from dried tucumã fruit; one serves as their wedding ring.

The land at Ecovila Iandê is lush with green leaves and vibrant fruit: cocoa, bananas, acai, and achiote. The property is adorned with reused material, as well – like the green and brown glass bottles cut into windchimes. The organization now runs one of the few community-supported agriculture (CSA) programs in the north region of the country, selling organic produce to families in the nearby city of Belém that have pre-paid for the harvest.

As part of the cotton project’s partnership model, FARFARM covers the free training to local farmers at Ecovila Iandê so that they can learn how to grow cotton organically through agroforestry methods. Beto Bina, FARFARM’s founder, describes the training as “an MBA for smallholder farmers.”

A key lesson is that agroforestry is all about experimentation. Oliveira has experimented over the years with the design of agroforestry farms. Now, she has templates for how exactly cotton farmers should organize their land to maximize both the growth of their cotton and the forest.

“A key lesson is that agroforestry is all about experimentation.”

Helping farmers to implement these methods successfully has contributed to a self-sufficient ecosystem in which smallholders now learn from each other, even outside of structured training programs. Local farmer Maria do Socorro, for example, is growing cotton for the first time this year after being inspired by her neighbor, Cesar Souza, who was farming with agroforestry.

She’s excited to plant trees that’ll not only provide colorful fruits to sell year after year but also an aesthetic for her land. She finds the agroforestry approach to farming “beautiful.” The visual appeal of yucca, flowers, and cotton growing in clean lines is part of what drew her into the work.

Do Socorro’s mom used to farm, too, but her methods involved using blazing fires to burn plots after the harvest to clear and nourish the land. Those same ferocious flames, however, also chip away at the forest’s stunning expanse – all while releasing the carbon once stored in its tree trunks. Though the farmer’s strategy has changed, she still cherishes her mother’s memory when she’s out on the land.

Health plays a big part in why many farmers are looking to organic methods. It’s non all about offering environmentally friendly products to clothing and apparel companies – they also want chemical-free food to eat and sell. They want to skip the pesticides and toxins they believe are endangering their bodies and communities. And they want to end agricultural burns that pollute the air.

The women of Cooperativa D’Irituia say that cancer remains one of Irituia’s top diseases. The mother of Nayara Leão, the cooperative’s cotton and organic certification coordinator, had breast cancer. She’s now cancer-free. The daughter of cooperative president Mariângela da Cunha Borges was also diagnosed with cancer at 14. She’s cancer-free now, too. This is why the cooperative focuses heavily on health. Every last Friday of October, the women plan a day-long event on breast and prostate cancer awareness where they teach local women how to conduct breast exams and also help men break stigmas around checking for prostate cancer.

“During our capacity-building training, we talk not only about agroforestry and cotton but also about health and protection,” Leão said.

“During our capacity-building training, we talk not only about agroforestry and cotton but also about health and protection.”

The cotton ecosystem in Brazil illustrates something we often forget about the items on store shelves – they are the products of both land and livelihoods. Every day in the field, workers have to walk around ant holes and bee hives. They toil beneath the sun. Sometimes, they even opt to work barefoot. Cotton is not a plant that simply grows – it is a plant that must be tended to: pruned, watered, harvested. The items in our wardrobes are not only something to wear – they are items that must be created, and agriculture is often the beginning of that lifecycle.

By incentivizing organic farming and agroforestry, FARFARM has given the fashion industry an alternative model to support. It’s also given local farmers a financially viable alternative to the monoculture farming that has contributed to the Amazon’s devastation. And most importantly, it’s building resilience – as the forest loses tree cover and moisture, it’s slowly converting to a drier savannah ecosystem, and agroforestry is one way to overcome the region’s increasing dry spells.

The start-up hopes that more fashion brands see the value of incorporating materials grown responsibly and invest in farmers who want to nourish the land, rather than exploit it. “Connecting smallholder farmers with brands is my life journey and what I believe the world needs,” said Bina.

Already, his theory is proving true. Cooperative leaders say they are seeing the health of community members improve. They’re eating more organic produce and abandoning their annual burns. These women want the world to know that what we buy has consequences. Our shopping habits often harm people. Sometimes, however, what we buy can give back to the community in bountiful ways.

“We can’t scream loud enough for the world to hear us,” said Maria Fernanda de Oliveira Lima, Cooperativa D’Irituia’s secretary, in Portuguese through a translator. “Our stories need to be told.”

“We can’t scream loud enough for the world to hear us. Our stories need to be told.”