Growing Cotton in Harmony with Nature in the Büyük Menderes River Basin, Türkiye

Photographer Anass Ouaziz joins Textile Exchange to visit the Büyük Menderes River Basin in Türkiye to document how cotton farming is impacting the area’s rich biodiversity. Alongside WWF-Türkiye, they see how regenerative practices can integrate local farmers into an agricultural system that gives back to nature instead.

Known to the Ancient Greeks as the Maiandros (Μαίανδρος), Türkiye’s Büyük Menderes river winds its way over 584 kilometers from the Western Anatolia region to the sea on its Aegean coast. It has long been characterized by its leisurely oscillation, so much so that its name Menderes forms the root of the modern English verb “to meander.”

Today, the Büyük Menderes river basin houses a wealth of habitats and biodiversity hotspots. Its delta is an internationally important wetland, where the river meets the sea in an intricate marbling of land and water. Bafa Lake – a former gulf now separated from the sea by sediment – is a haven for visiting birdwatchers and local fishermen alike. Both are home to endangered species including the Dalmatian pelican and European eel.

But the river basin is known for more than just nature. Home to a thriving textile industry and over 42 mills, the land around its sweeping curves also represents the second-largest cotton-producing area in the country. Nested between the delta, Bafa Lake, and the Latmos mountains, the cotton fields of the Soke Plain alone support the livelihoods of approximately 30,000 people.

Often, the activities used for cotton cultivation are at odds with the local ecosystem. From blocking the Büyük Menderes’ natural flow to pool resources for flood irrigation, to polluting the lake with the runoff from synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, the impacts of industry and agriculture are reflected in its waters.

“To understand the risks of farming, you have to go beyond the farms” explains -Eren Atak, the Freshwater Program Manager at WWF-Türkiye, leading its work in the area. Driving through the Soke Plain at harvest season, she points out where some of the problems arise.

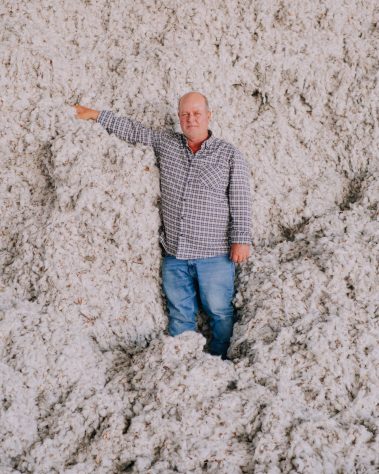

While trucks and warehouses are brimming with freshly harvested fibers, the fields are brown and bare, their soil dry, cracked, and left exposed to the elements over the winter. On some plots, late blooming bolls still cling to defoliated stems – on others, machinery is already at work to till the soil or flatten out the fields in preparation for the use of flood irrigation.

Farming in harmony with the local ecosystem

As part of its program in the Büyük Menderes basin, WWF-Türkiye is setting out to show the textile industry that there is a way to produce cotton that gives back to the local ecosystem instead. One solution comes in the form of two pilot plots of land in the Soke Plain, where it is working alongside local farmers and a team of scientists to grow cotton with increased respect for soil, water, and nature.

The first plot is situated at Söktaş, a farm in the small village of Sazlı where farmers have been trialing regenerative practices for five years and working alongside WWF-Türkiye for three. Here, the cotton fields are set against a mountainous landscape, interrupted only by the silver pipes of the farm’s center-pivot irrigation system. It’s currently being tested as a more water-efficient alternative to flood irrigation and is the first sign of the owners’ willingness to find ways to grow cotton that respect the local resources, rather than depleting them.

“We are the owners of the soil, and this is our responsibility,” explains İrfan Uysal, who manages the plot, where low and no-tillage /methods are used and agricultural chemicals are minimized in favor of homemade compost. “We have this resource, and we have to take care of it.”

A few steps into the field further reveal what this looks like in action. The soil is covered under a blanket of mulch, made from a decomposing mix of cover crops like turnip, wheat, pea, and sorghum that protects it from rains and erosion. Grown on the land in the spring before the cotton was planted in their place, each provides it with a unique service, from boosting nitrogen to increasing aeration.

“You can see the biodiversity in the soil – it’s alive,” remarks Uysal, describing the myriad of creatures that have made the mulch their home. “I’ve been farming cotton for 30 years, and this is the first time that I’ve seen earthworms,” he adds, noting how each organism adds value to the soil’s ecosystem and increases its quality.

Observing outcomes from both the land and the lab

Other observations hide under the soil’s surface, only to be made when the cotton plants are pulled up to reveal their roots. “When the root of the plant grows vertically down, it means the soil is more aerated and less compact,” explains Dr Erdem Aykas, a professor at Ege University’s Faculty of Agriculture specialized in farm machinery, and consultant on the pilot. He checks several, and – accepting that achieving the results he wants will take time – sets the specimens and their still slightly unruly roots back down.

Lessons from the land are backed up with data from the lab, where the team closely monitors indicators like soil carbon levels, soil organic matter, aggregate stability, salinity, water holding capacity, and irrigation water efficiency, among many others.

This data is tracked alongside the farmers’ observations in a holistic monitoring approach where worm count – which has increased from zero to 100 per square meter by 10 centimeters of soil in the last two years – is just as important as outcomes like soil pH and porosity.

This careful balance of farm know-how with science and academic expertise helps optimize the practices that are used on the ground. Take the process of growing the cover crops and leaving them on the fields as mulch. To improve how this is done, Dr Aykas led the development of specialized roller crimper machinery, designed to fold the cover crops over before cotton planting begins, allowing them to remain on top of the soil. This process is followed by another no-till farm machine he developed, that cuts open the organic matter and sets the cotton seeds in place.

A similar system of testing and optimizing has been applied to making and applying the compost. “We started by using the recipe from the Soil Food Web School,” explains Iraz Candas, the project’s soil microbiology consultant. “Then we designed and tested a system to apply it that won’t kill the biology in the compost.”

Applying learnings in different geographical contexts

While the team might have landed on local recipes for success, one thing they know for certain is that no plot of land is the same. Methods must be tested in multiple locations on different types of soil, and adapted to the context in which they are used.

The second pilot plot is situated by the sea near the village of Tuzburgazı, offering the team the opportunity to trial their learnings on saline soil with a low organic matter content. It is part of Tanmanlar Agricultural Enterprise – a three-generation family that first got involved with WWF-Türkiye through its work with Better Cotton.

Here, the saltiness of the soil initially proved a challenge for the farmers. “The yields decreased for the first couple of years, at the beginning of our learning process,” recalls Fuat Tanman, who runs the farm as well as sitting as the chair of IPUD, Better Cotton’s strategic partner in Türkiye. “And so you have to be prepared for that.”

Despite the initial difficulties, Tanman persevered with the cover crops and compost recipes optimized with help from WWF-Türkiye and its consultants. Now the pilot is in its third year, and signs of success have started to show. “Usually in this area, the soil organic matter is below 1%,” he explains. “Here, it was 0.8%. But since we’ve been trialing the regenerative practices over the past three years, we have seen it rise to 1%.”

These subtle changes can be observed in the day-to-day management of the farm as well. Metin Samkose, one of the workers who manage the regenerative plot, illustrates the beneficial impacts on the land that he is observing through the concept of “şeytan yolu” or devil’s path – a term used among local cotton farmers to refer to strips of land in which the soil is so depleted that nothing can be grown. “Here, even the seytan yolu is starting to become fertile,” he explains with surprise, as dragonflies circle the lush green field in which he is standing.

Creating a financial safety net for others to experiment

Like Söktaş, Tanmanlar Agricultural Enterprise is big enough to be able to dedicate specific plots to trialing these methods and observing the results, taking the financial risk of a learning-from-doing approach. But decreases in yield are a steep price to pay for soil health, and one that they recognize smallholder farmers cannot shoulder.

“I would like us to be able to inspire other farmers, but it’s so important that smallholders have financial support because while everyone’s soil is different, not everyone can allocate land just to try and test things,” adds Samkose.

Uysal at Söktaş shares a similar sentiment: “We are working with academics, and we are observing the results. We see that this is the right direction, but we’re trying to find the right way to move this journey forward.” He too notes that finance will be key, and that government subsidies for regenerative practices could help.

This is important to WWF International’s vision for the long-term outcomes of its work in Türkiye. The project is part of its global mission to lead the adoption and implementation of water stewardship in the textile sector, and it is running water stewardship programs in countries like China, India, and Vietnam too. With the support of brands and local partners, it hopes that the efforts to test regenerative practices at pilot scale in the Soke region will help to influence policy development around financial support for interested farmers in Türkiye.

To set this in motion, WWF-Türkiye is beginning to diffuse the pilot learnings through a video series for farmers. Currently available on YouTube in Turkish, with English on its way, the series includes everything from compost recipes to simple on-farm soil tests. Beyond the farm gate, the team has facilitated the formation of the Söke Cotton Water Stewardship Committee, which aims to address the wider water problems in the area, and designed another pilot project, this time using modern irrigation systems.

Ultimately, an ecosystem like the Büyük Menderes basin requires a landscape-level approach, and the project’s success will depend on its ability to help inspire and educate others in the region to farm with increased respect for the resources around them. But as climate change threatens the resilience of conventional farming practices in the future, with increasing droughts and unpredictable weather, it almost feels like a shift in the system could be inevitable.

While the hope is that WWF-Türkiye’s pilots will pique local cotton farmers’ interest, encouraging peer-to-peer learning and community building, the team knows that it will take time, and most importantly – investment from the industry that uses the materials they produc“When we as farmers think about what we can do in the face of climate change, one of the key things is to implement these kinds of agricultural practices that help to protect the local ecosystem” summarizes Tanman. “But we do need a financial safety net in which to do so.”

Explore the FUll Series

Cultivating Cotton in a Key Biodiversity Area

Anass Ouaziz was the runner-up of our 2022 photography competition with Magnum Photos, which called on photographers to explore the visual stories that take place when fibers and materials are cultivated, created, spun, woven, sewn, loved and cherished – gaining cultural and emotional significance through the journey.